Sarah Palferman shares with us another feature on why art exhibitions are brilliant for young minds. Sarah has the gift to harness our children’s sponge-like minds to absorb and learn about art in the most interesting of ways. I cannot wait to take my children to London to expose them next summer to the galleries with Sarah.

“I never teach my pupils. I only attempt to provide the conditions in which they can learn” – Albert Einstein.

There are more than 850 art galleries in London. The city’s wealth of culture might, therefore, rather easily overwhelm even those of us who schedule furtive ‘gallery time’ into the working week. This is particularly true if you are a child and the very word “gallery” might render you instantly fatigued.

It has been argued that art exhibitions are no places for children and, while anyone whose contemplation of a sublimely silent Dutch interior has been shattered by the noisy protestations of young visitors being dragged round London’s National Gallery might agree, I do not.

Those noisy protestations are unnecessary. Done the right way, it is perfectly possible to engage young people with art so that their curiosities are sparked, their wonderfully sponge-like brains are stimulated … and they have fun!

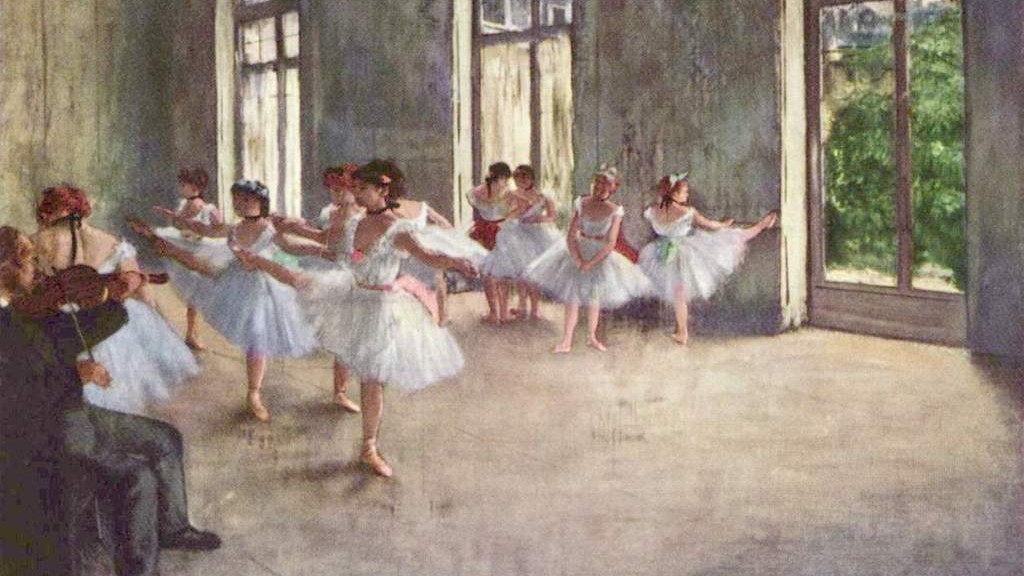

Human beings are hardwired for stories. We have told them to each other since the dawn of time; we have written about them in literature from the Epic of Gilgamesh inscribed on clay tablets in ancient Sumer onwards; we depict them in music, theatre and dance; and we express them through visual art.

Behind so many canvases and sculptures lining the walls of London’s galleries lurk fascinating stories waiting to be discovered: scenes of scandal, war, revenge, love; canvases with their own tales of tragedy and fables of forgery; art that might or might not even qualify as art.

It is hard, for example, not to be moved by Waterhouse’s symbol-sprinkled and gorgeous depiction of the ill-fated Lady of Shalott, frozen in Tate Britain moments from her demise. The power of this tale to enthral is evident in the layers of inspiration from Arthurian legend through Tennyson’s poetry to Waterhouse’s paintbrush.

The National Gallery is heaving with portrayals of myth: Daphne mid-transformation into a laurel tree as an arboreal escape from the attentions of Apollo; Bacchus mid-leap from his chariot, struck by a coup de foudre on discovering the abandoned Ariadne; the Rokeby Venus mid-languid gaze at the viewer and fully recovered from her attack with a meat cleaver at the hands of a suffragette in 1914.

At the Courtauld Gallery skulks The Procuress, the subject of decades of speculation and revealed by clever modern investigative techniques to be the handiwork of a somewhat talented twentieth-century Dutch forger rather than of an early seventeenth-century painter of original creations, also Dutch.

Focusing on just a few pieces and exploring them together in depth is far better than parading children round vast rooms of great masterpieces and, even worse, telling them that these are ‘Great Masterpieces’. Research conducted in the USA 犀利士

over the past decade concluded that the study of the visual arts allows young people to explore ideas, realities and relationships that cannot be conveyed simply in words. Through visual stories, children can explore concepts beyond their own environments and appreciate alternative viewpoints. They are exposed to different cultural perspectives and social groups in entirely unthreatening circumstances. They can develop a sense of themselves in relation to others and the world they inhabit.

Captivating young imaginations with the stories behind art, and keeping each cultural encounter clearly focused so that repeat visits are begged, removes the danger of dissociation from artistic tradition that many children might experience. It endows them with a sense of wonder without the risk of paralysing awe, or even worse, scant interest. It allows them to see themselves as part of a cultural continuum, with the capacity to engage in a journey of discovery that will enrich their whole lives.

Sarah Palferman is a private tutor and educational advisor. She is the founder of Minerva London Ltd, offering tailored adventures in art and culture to young people in London.

To find out more, please visit

or email